Preface

Is OCaml hard to learn? Yes and no. It's easy to learn because it's not a “puzzle language” — its rules are generally hard and fast, and its syntax and semantics are predictable. However, it's also harder to learn than most popular languages because it uses ideas that are only starting to gain wide acceptance. It is not unlike the difference between the assembly languages and first structured programming languages.

Why would one want to use it? Here are some points:

- Very fast compiler. The reference implementation of OCaml can bootstrap itself within minutes.

- Static typing without a need to write any type annotations by hand.

- The type system is expressive enough to find some classes of logic errors, not just misplaced variables.

Its traditional domain is compiler writing and automated theorem proving systems. For example, Coq proof assistant, that was used to create the first C compiler where all optimizations are mathematically proven correct, is written in it. The Rust compiler was written in OCaml until it was able to compile itself.

More recently, it also started to be used by financial companies such as Jane Street and Lexifi for their automated trading software, and tools for cross-compiling it to JavaScript allowed using it for web applications. For example, the web version of Facebook Messenger was largely rewritten in OCaml with alternative syntax.

→ A bit of history

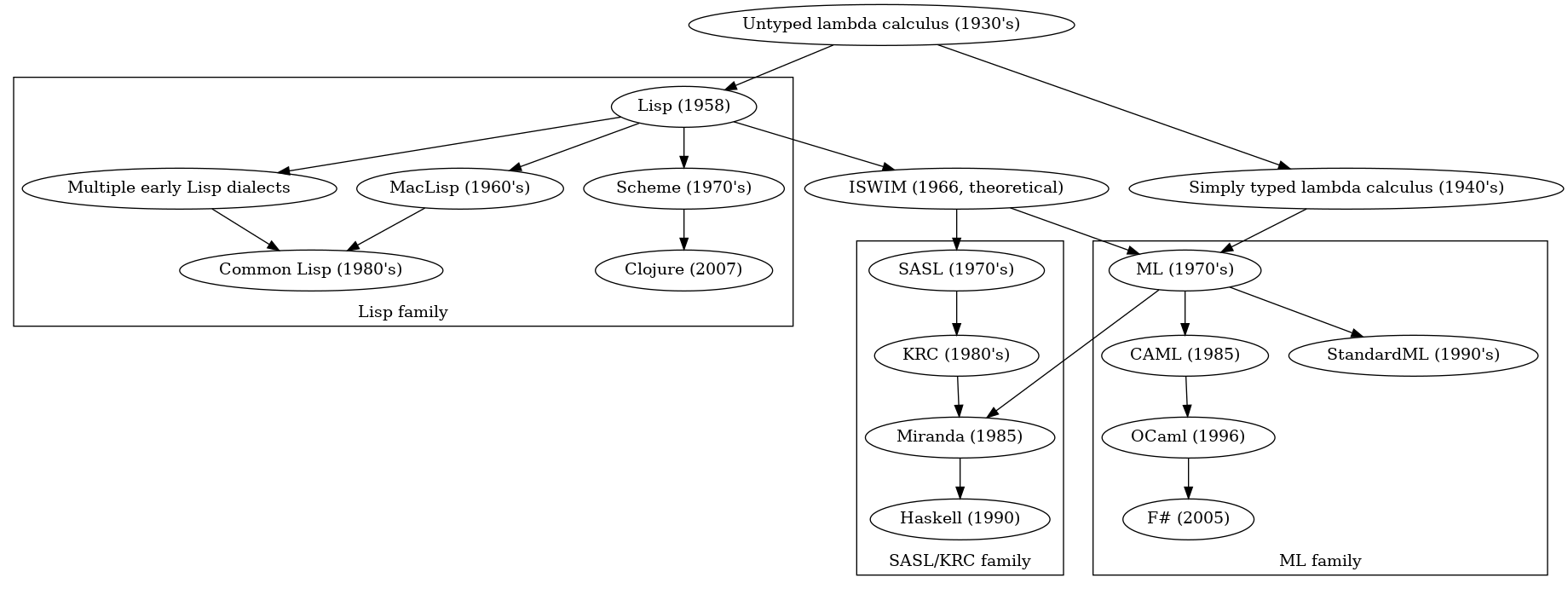

OCaml itself is not new. It was first released as a distinct language in 1996, and even has one direct descendant — F#, that even includes syntax compatibility mode. However, the history of the ML language family is even longer and goes back to the 70's, and the theory that made those languages possible is even older yet, dating back to the 30's — it is called the lambda calculus.

Here is a brief and simplified story.

In the 30's, mathematicians took intense interest in the concept of computability. They could be called computer scientists even though general purpose computers didn't exist yet, and they were creating the foundations for their development. The main questions of the computability theory are what problems can be solved by algorithms, and how to reason about algorithms, for example, how and when can we find out if an algorithm always terminates. It required computation models, and multiple models were developed independently.

Alan Turing developed the well known abstract machine that is now called Turing machine — an infinite length tape and a head that can read and write symbols to the tape cells. Independently, Alonzo Church and Haskell Curry found that it is possible to model arbitrary computations using nothing but functions — that was the lambda calculus. Then it was discovered that the two models are equally powerful.

In the 40's, the lambda calculus was extended with a concept of types. Types were invented even before the lambda calculus, and long before computers, as an alternative to the set theory that would be free of its paradoxes (Bertrand Russel, who discovered a famous paradox, worked on type theory extensively). However, it took a while longer for the typed lambda calculi to take root in computers languages, and the first languages based on it were untyped.

The Turing machine is roughly the model behind imperative languages such as C and Fortran. The first language closely related to the lambda calculus was Lisp developed by John McCarthy in 1958. For a while, all functional languages were untyped (or dynamically typed).

However, in the 1970's, J. Roger Hindley and Robin Milner independently discovered a type system that allowed to unambiguously infer types of all expressions in a language without any type annotations. Then Milner et al. developed an algorithm for doing it efficiently, and created a programming language called ML (Meta Language) that was statically typed but made type annotations entirely optional, since it could infer all types and detect type errors on its own.

Initially, ML was an embedded language of a theorem proving system, but later took a life of its own, and people (I need to research who did it first) discovered a way to extend it with mutable references and exception handling in a type safe manner at cost of a small restriction. Now it was suitable for general purpose programming.

ML had multiple descendants, most of them research languages not intended for production use. Its type system was also incorporated into the family of programming languages that led to creation of Haskell, though whether Haskell belongs to the ML family or not is debatable.

The original ML went through a process of standardization in the 1990's and its entire specification was mathematically proven to be consistent by Robert Harper et al., which is a truly outstanding result. However, its specification was not extended since 1997, and it's rarely used now, even though it remains fairly popular for teaching and a few theorem proving systems still use it. One notable modern project that uses it is Ur/Web, a specialized programming language for web development.

Another ML descendant called CAML remained under active development, and eventually evolved into OCaml we know today. Along with F#, it remains the most common ML in production use now.

→ The implementation

OCaml is probably unique in that its reference implementation includes all of native code compiler for multiple platforms, a bytecode compiler, and an interactive interpreter. Standalone program normally use the native code compiler, while the bytecode is only used on platforms not supported by it, With third-party tools, it can also be cross-compiled to JavaScript, and the tools are powerful enough to allow running OCaml itself in the web browser, you can find a real example of it at try.ocamlpro.com.

The implementation is licensed under GNU LGPL and is available from ocaml.org. On UNIX-like systems, however, the fastest and most convenient way to install it is to use OPAM, the OCaml package manager. Unlike most similar tools such as Python's pip or Haskell's cabal, OPAM allows installing the compiler itself, keeping multiple compiler versions on the same machine, and switching between them, in addition to installing OCaml libraries.

OPAM for Windows, however, is still under development, so I will not cover it yet.

When you have OPAM installed, use the opam switch command to install the compiler. At the time of writing, the latest version is 4.07, so the

command will be: opam switch 4.07. When it completes, you may want to run this command to setup the environment varibles without restarting your shell:

eval $(opam config env).

Once you are set, you can verify the installation by executing the three main programs: ocamlc (the bytecode compiler), ocamlopt (the native code compiler),

and ocaml (the interactive interpreter). The first two should exit without any output, the third one starts the interactive top level where you can

enter expressions and have them evaluated — more on that later.

→ Using the REPL

The interactive interpreter allows you to enter expressions and have them evaluated. One thing you should note is that it uses double semicolon

as an end of input mark, so you should terminate all expression with ;;.

The default REPL is quite minimalist and doesn't even support command history. You can either alleviate the issue with rlwrap,

or, better, install utop from OPAM (opam install utop). It is an alternative REPL that supports history, completion, and more.

While the examples here tend to be compiler-centric, you should not neglect the REPL. First, it's the quickest way to find out the type

of any function without even opening the documentation: just type something like print_endline ;; and you'll see the type.

Second, any valid OCaml program can pasted into the REPL or its file can be loaded into it with #use "somefile.ml";; directive.

It is even possible to run OCaml programs in the same fashion as Python or Ruby scripts with ocaml file.ml.

It is also possible to load compiled libraries into the REPL, but we'll not discuss that part now.