Algebraic data types and pattern matching

- Product types

- Sum types

- Pattern matching

- Patterns in let-expressions

- Match expressions

- Nested match expressions

- A note on exhaustiveness check

- Exercises

So far we've only seen types that can encode single values, such as integers, strings, or functions. Practical programming, however, is nearly impossible without composite types. Tuples, lists, trees, and other datastructures are staples of software development.

The most common building blocks of composite types in OCaml are so called algebraic data types (ADTs). While OCaml has records, objects, and arrays too, the most common built-in types are ADTs.

Algebraic types are closely connected with pattern matching and explaining them has something of a chicken and egg problem: it is impossible to explain pattern matching without explaining algebraic types, but algebraic types make little sense until you know how to use them in pattern matching. We will try to break the circle by learning how to define them by example, and then learning how to actually use them.

→ Product types

Product types are also known as tuples. They get their name from their relation to the cartesian product of sets. A cartesian product of two sets A and B is a set of pairs of all items of A and B. For example, a plane is a product of a line with itself.

This is how we could define a type of points on a plane:

type point = float * float

Note that while you can define a named product type, they are usually left unnamed, and if you call a float * float

type point, the OCaml compiler will not start referring to any value of type float * float as point.

The * operator is a type constructor that creates a new product type from two other types, in this case

a tuple of two floats. You can create tuples of more than two items in the same fashion:

type point3d = float * float * float

This is just the type though, and naming product types is not a standard practice. Values of product types use comma as an item separator, like in many other languages. Note that parentheses around tuples are optional and required only when leaving them out will cause ambiguity.

let zero = 0.0, 0.0

→ Sum types

Sum types generalize what is often known as enum, union, or variant record. They are also rather harder to explain than product types because they have no direct equivalent in most languages.

Mathematically, a sum type is a disjoint union: a union of sets where every element is attached to a tag indicating which set it came from.

The simplest kind of a sum type is used to model finite sets. This is equivalent to enums in C-like languages.

type chess_piece = Pawn | Knight | Bishop | Rook | Queen | King

This is the simplest use case however, and their greatest expressive power comes from the ability to attach values to sum type members. For example, suppose we are writing a geometry program and we need a type for shapes. A circle can be defined by its radius, a square by its side length, and a triangle can be defined by lengths of its sides. So our type may look like this:

type shape = Circle of float | Square of float | Triangle of (float * float * float)

Sum types can also be polymorphic. For example, there is a type in OCaml standard library that is meant for functions that can produce some value or no value at all, it is called option. For example, searching for something in a database can produce a list of results, or not find anything, and it is nice to be able to encode the latter case explicitly. The option type can be defined as follows:

type 'a option = Some of 'a | None

There is also a type meant for functions that can explicitly signal error conditions:

type ('a, 'b) result = Ok of 'a | Error of 'b

As you can see, polymorphic types need to have one or more type variables on their left hand side.

→ Terminology and syntax

You should remember that user-defined data constructors must always start with a capital letter.

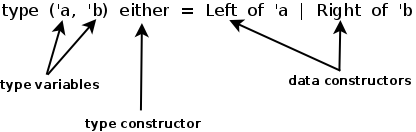

The anatomy of a sum type definition is shown in the following picture:

The name of the type is referred to as type constructor, because it can be used to create new monomorphic types

with different type variables, such as int option or string option, or (int * string) result and

(float * unit) result.

Names of sum type members are called data constructors, since they can construct new values from existing ones,

such as Some 3 or Error "Not found".

→ The truth about unit and boolean values

While there is special syntax for the unit value () and boolean constants true and false,

internally, they are just sum types.

If special syntax didn't exist for them, they could be defined as:

type unit = Unit

type bool = True | False

→ Pattern matching

We have already seen some basic use of patterns, and learnt that the left hand side of let-bindings,

including function definitions, is a pattern.

Here is what we know is a valid pattern:

- A variable name

- A constant

-

The wildcard (

_).

Now we can add that a tuple, any defined data constructor, and any combination thereof is also a valid pattern.

→ Patterns in let-expressions

Let's see how we can use tuple and data constructor patterns in let-bindings.

Some languages have special constructs for multiple assignment.

In OCaml, you can do the same by using a tuple pattern, so no special construct is needed.

let a, b = 1, 2 in

Printf.printf "%d %d\n" a b

If you have a function that returns a tuple, and you only want one item of that tuple, you can combine the tuple pattern with the wildcard pattern to discard the unwanted part:

let f x y = x, x + y

let _, x = f 3 2

let y, _ = f 3 2

let () = Printf.printf "%d %d\n" x y

The relationship of let-bindings with sum types is more complicated. While they can technically be used on the left hand

side of a let-expression, if your type has more than one data constructor, it will result in unhandled cases,

which will result in compile time warnings and runtime errors.

Consider this program:

let x = None

let (Some y) = x

let () = Printf.printf "%d\n" y

If you compile and run it, or paste into the REPL, you will get this warning at the compilation stage:

Warning 8: this pattern-matching is not exhaustive.

Here is an example of a case that is not matched:

None

And at the execution stage it will fail with Match_failure exception. While you could catch that exception

(we will learn about exceptions later), it would be a very unidiomatic thing to do. Types with more than one

data constructor should be handled by proper cases analysis with match expressions that are covered by the

next section.

The unit type is an exception to this rule, since it has only one possible value and thus immune to match

failures. That is why it can safely be used in let-expressions when you want to enforce that the expression

on the right hand side evaluates to unit.

→ Match expressions

In OCaml, match expressions play a role similar to case or switch in many other languages, but

due to pattern matching support, have more expressive power.

Their simplest use can be demonstrated on primitive types, such as int. Constants of any type are valid patterns,

and we can match on them.

Let's compare functions that

determine is given number is zero, written with a conditional expression and pattern matching:

(* With a conditional *)

let is_zero n = if n = 0 then true else false

(* With a match expression *)

let is_zero' n = match n with 0 -> true | _ -> false

In multi-line match expressions, some people like to add a | character before the first case as well, for

visual uniformity:

let is_zero n =

match n with

| 0 -> true

| _ -> false

A function determines if given character is a whitespace character or not can be a more interesting example:

let is_whitespace c =

match c with

' ' -> true

| '\t' -> true

| '\n' -> true

| '\r' -> true

| _ -> false

You can see that it's rather repetitive. To avoid repetition, OCaml allows conflating cases:

let is_whitespace c =

match c with

' ' | '\t' | '\n' | '\r' -> true

| _ -> false

So far this is equivalent to switch statements in C-like languages, so let's move on to

more interesting patterns that allow us to destructure complex values.

To demonstrate using tuple patterns inside match expressions, we will reimplement the logical AND function.

Logical AND is only true when its both arguments are true, otherwise it's false. With a match expression

and a tuple pattern we can express it concisely:

let (&&) x y =

match (x, y) with

| true, true -> true

| _, _ -> false

We could use nested matches, but that would be unwieldy. Instead, in the match expression,

we join both arguments into a tuple so that we can match on them both at the same time in our

cases, and this way we need only two cases.

Now let's see how we can combine data constructors of sum types and tuples in pattern matching. Remember the type for geometric shapes that we introduced earlier. This is how we can write a function for calculating the area of different shapes:

type shape = Circle of float | Square of float | Triangle of (float * float * float)

let area s =

match s with

| Circle r -> Float.pi *. (r ** 2.0)

| Square s -> s ** 2.0

| Triangle (s1, s2, s3) ->

let s = (s1 +. s2 +. s3) /. 2.0 in

sqrt @@ s *. (s -. s1) *. (s -. s2) *. (s -. s3)

let () = Printf.printf "%f\n" @@ area (Triangle (3.0, 4.0, 5.0))

→ Nested match expressions

In the logical AND function, we managed to get away with a single match expression,

but there are cases when nesting them is unavoidable. The issue you should be aware of is that,

since indentation in OCaml is not significant, nested matches need explicit delimiters.

Like any other expressions, you can wrap them in parentheses, but there is also syntactic sugar

in form of begin and end keywords. They are syntactically equivalent to parentheses, to the point

that the unit value can be written as begin end, as in print_newline begin end, though using them

in this role is obviously bad for readability. But for grouping expressions, they can provide

a readability improvement.

Let's rewrite our logical AND function in an overly verbose way for demonstration.

let (&&) x y =

match x with

| true ->

begin

match y with

| true -> true

| false -> false

end

| false -> false

If you forget to group match expressions properly, they will be treated as one long match, which

may cause type errors, or, worse, break your program logic.

→ A note on exhaustiveness check

As we have already seen, the OCaml compiler performs match exhaustiveness checks and warns you if it finds

a case that is not handled. The checking mechanism is consistent (free of false negatives), that is, it will never fail to spot a

genuine unhandled case. However, it is not complete (not free of false positives), and sometimes will

issue warnings when matching is actually exhaustive. This happens especially often if you use nested match expressions.

The compiler warnings must be taken seriously. Only if you can prove that your matching is indeed exhaustive, then you can safely ignore them.

→ Exercises

Write a function twice that takes a function f and a value x and applies f to x twice.

Try to predict its type before you check it with the REPL or another tool.

Simple: write a function with type 'a -> unit.

Somewhat harder: write a function with type ('a -> 'b) -> ('b -> 'a) -> 'a -> 'b.

Define a sum type that models a card deck.

Using a match expression, write a function is_vowel : char -> char that checks if given

character is a vowel.

Write a function with deliberately non-exhaustive pattern matching and cause it to fail with Match_failure exception.

Write a logical XOR function using a match expression and no more than three cases.

Extend the shape type and the area function with one or more new shapes of your choice.